Two Speeds

Since I turned 7 and for my entire childhood, video games were my favourite thing, my main hobby.

The release of a new console was a monumental moment: when I got a Super Nintendo, I remember the excitement - it was a real event. Getting new games in a small town on an Italian Island was not always the easiest thing; I remember obsessively waiting for my copy of NBA Jam for the SEGA Mega Drive and calling the shop every day to check if it had arrived. I am sure they loved me.

Prehistoric Video Game Journalism Artefacts

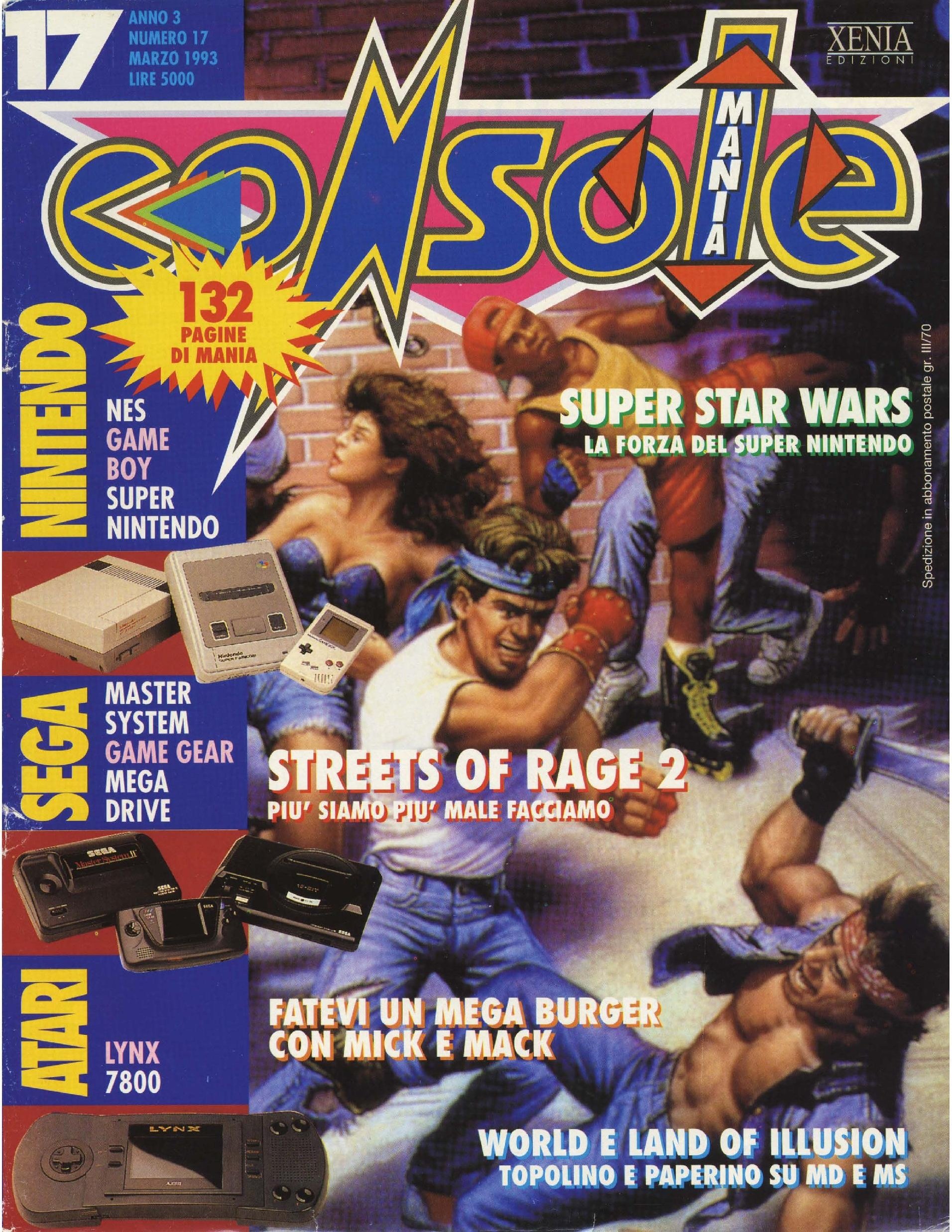

As a young fan, video game critics were among my heroes. I started buying magazines like ConsoleMania, Game Power, Zeta or CVG when I was eight or nine years old, and the idea that there were people whose job was to write about video games for a living was mind-blowing to me. I bought some international magazines, from US and UK, even if my English skills, at the time, were beyond basic.

In the pre-internet era, that was the only way to get information about something I loved. I had no career aspirations at that point, but I am pretty sure that becoming one of those journalists would have been pretty high on my ranking of jobs.

But this passion simmered a bit during my high school years. I got more into movies and music, and even if video games were still a part of my life, I stopped focusing on them, buying all the video game magazines, and skipping the 32/64 era. It happens a lot that in high school one tries to figure out what being an adult means, and experiments with doing away with the things they had loved as children; a moment of transition, before you grow up and realise being an adult means choosing your path and accepting that life is always transitory. And at some point, I realised that I had a goal, and it was to make movies. Video games would go to the rearview mirror.

For a while, my connection to movies was, just like video games, partially mediated by criticism: I was a movie fan trying to develop my taste as a movie fan, and this meant reading movie magazines and buying film encyclopedias. Maybe it is because my father is a journalist, but I gave a lot of importance to expert opinions about art. As I started to become serious about making movies, this became part of my education as well.

After all, if Francois Truffaut became a filmmaker after being an influential movie critic, there must be a correlation between the two. I thought.

Life after school often runs at a slower speed than you expect, and unexpected things happen. My plans to become a filmmaker were going to kick off right after high school, but some life events made it so that it would have to wait for me to graduate from university.

I had to spend more time in my home town, I had a lot of free time, and I rediscovered my passion for video games by, among other things, becoming very active in a couple of Italian video game communities. At first, NextGame was the place I was spending most of my time in (sadly, that website, and its forum, are all gone). Then, famous Italian Video Game journalist Ivan Fulco started The First Place, his website, and I also became very active there. I loved that Ivan’s vision was to take video games more seriously, and to have fun by looking at them with a critical eye that was not just aimed at recommending what to buy, but treated the medium as something important and meaningful.

I've always been a decent writer. One day, after watching The 25th Hour, Spike Lee's 9/11 movie, I felt compelled to write a quick review of it, and I sent it to Fulco. He liked it, he published it, and from that moment on, I started collaborating with the website. What started as a hobby, eventually became a gig: Ivan connected us with some magazines he had a hand in, and soon after I also started writing articles for other magazines, mostly focusing on movies and video games.

I had accidentally fulfilled one of my childhood dreams; I also realised that video game journalism was not exactly as glamorous as eight-year-old me envisioned. Once, chatting with some of the writers that I worshipped when I was a child over some drinks during one of the first GamesCom, I heard some stories from their time as video game journalists in Italy in the mid-nineties - and I realised that some of my childhood heroes were teenagers whose working conditions would have been considered a violation of child labour laws under judicial scrutiny - yet, they looked back at these times with fondness: they were pioneers after all. And for me, to be part of that community was a great feeling. At some point, I even had an offer to move to a new city and work at a magazine as a full-time employee.

But there was something off about that. I liked criticism, but I also did not see it as my endgame. I loved art and culture, but I wanted to be part of it as a creative. For a long time, I did think that criticism and creativity were closely connected. But, as time passed, I was not that convinced about that anymore.

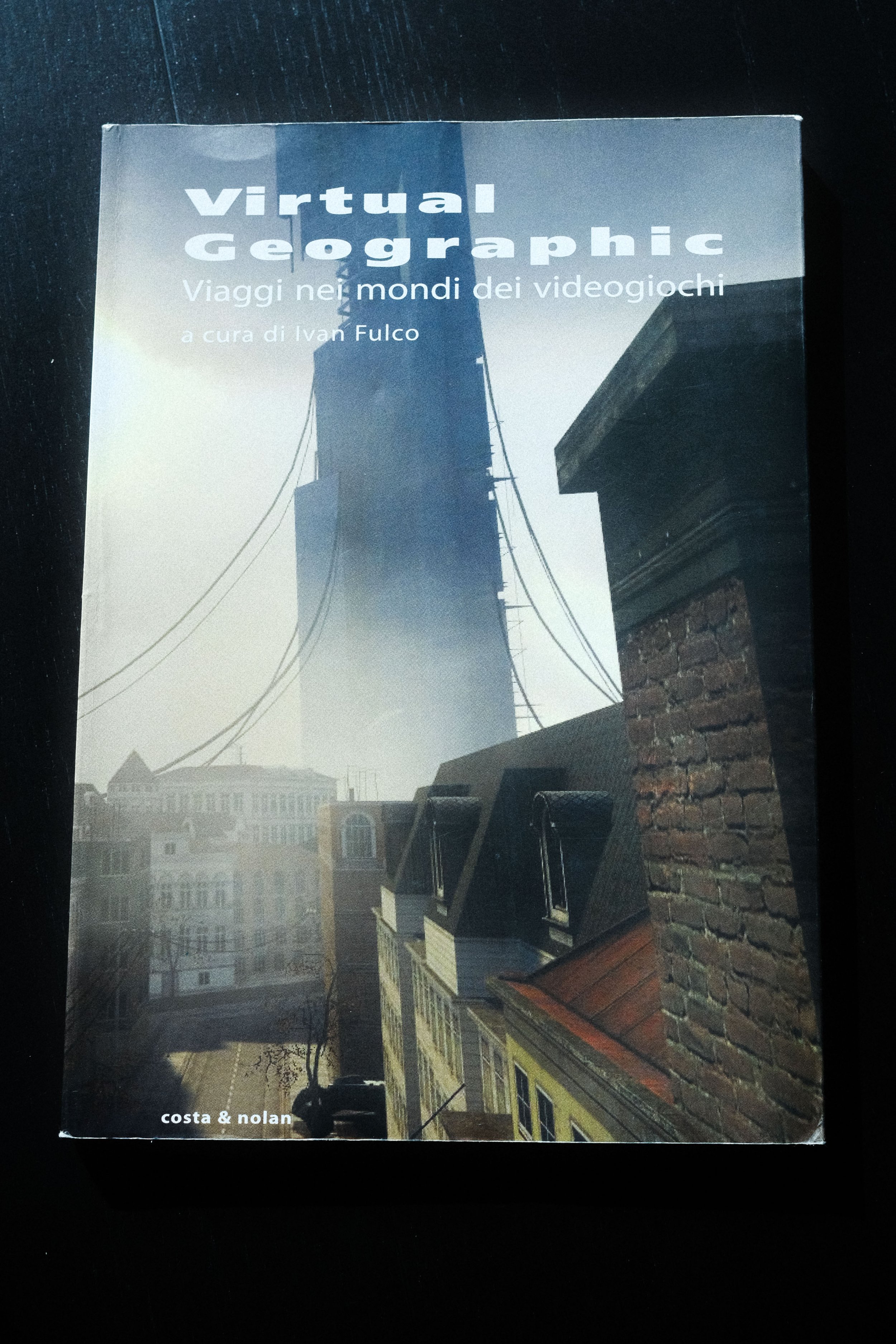

VIrtual Geographic

My favourite artefact from my career as a video game journalist is this book: edited by Ivan Fulco, with an intro from Matteo Bittanti, it’s a collection of photo and text reportages from video game worlds, partially inspired by an idea I had while writing for The First Place. I’ve contributed a couple of “reportages” to it.

The entire idea was to explore video game words beyond their role as a playground for game mechanics: to dive into virtual world-building, an art that today is even more developed and thriving.

At some point, another big life change happened and I went to film school and started making movies.

I realised very quickly that all of my critical skills were borderline useless when it came to creating art. It’s almost as if the process of making things and the process of experiencing them takes place in completely different parts of the brain. Even more, at times it was almost as if my critical mind would “push down” my creative side: making it second guess every idea, every choice.

It took me some time to learn to allow myself to be truly creative, To realise that it’s very important to allow yourself to have bad ideas, and to do that A LOT. Creativity is iterative: it’s about trying out a lot of things, relentlessly, before finding something in your life. And this process of trying only really works if one does not put any judgement over it and if they allow themselves absolute freedom to suck.

But for a while I was working both sides: I was still writing criticism often, and also working as a creative. It was a very interesting balance to work with, and I had to find strategies to jump between the two, and, at least for me, it was not especially easy.

For a while, a big part of my podcast diet was centred around listening to movie and TV podcasts that would spend often up to an hour discussing newly released movies or shows. There is something fun about watching something and immediately after hearing a discussion about it - it’s even better if you have friends to discuss with after watching a movie, but that is not something you can organise every day.

Most of these podcasts were made by amateurs, people with a decent knowledge of the medium; or even professional critics. After some time (too long, honestly), something struck me, though: my brain was becoming too acclimated in hearing critical thoughts that did not have a lot of substance, and that is not very healthy. Turns out, it’s very unlikely for anyone to have great insights about a work of art just a few hours after having experienced it. What you’re going to get is gut reactions that often reflexively reduce the breath of a work of art by trying to sum a complex experience into half-baked ideas. It’s a well-meaning process; but, after a while, I cut it off completely.

Now I only listen to podcasts (or video series) that have a healthy news and interview section and very brief reviews, or podcasts that go deep into a work of the past. These are the only two formats that allow for a healthy approach for the critic. More than that, I listen to a lot more content that talks about creativity and helps foster it.

But does my background as a critic also help me as an artist?

To a certain extent, it does. My ability to articulate my opinions of other people’s work did help in communicating what I liked and disliked about what I do, and also to give more precise directions to collaborators; it also refined my taste in movies, games, TV, and music. Being creative definitely made me a much better critic, on the other hand: understanding the process behind making art refined my understanding of the art itself, and allowed me to analyse it in much more precise and empathetic ways.

Curation over criticism

Reading this book (and Creative Quest as well) made me think about culture, and writing about it, in a very different way.

Questlove sees his mission as one of being both an artist and a curator: someone who helps people discover art, who helps contextualise it, enriching a conversation about culture just as much as he does by creating art.

This is also one of the impulses behind this website: bringing together curation and sharing creative work.

It’s good to see that platforms like Nebula are coming up to dedicate themselves almost completely to curation. There are elements of criticism here, but the approach is way more focused on discovery, and enlightenment; to give tools to make sure one accepts how complex reality is, without necessarily feeling overwhelmed by it. This kind of stuff does add to the creative process. It fosters it.