A list of movies that became great by embracing chaos.

There was a time when I believed that movies were the result of a very well-executed plan.

And sometimes that is the case, but most of the time, as Rober Altman used to say,

Making a movie is like chipping away at a stone. You take a piece off here, you take a piece off there and when you’re finished, you have a sculpture. You know that there’s something in there, but you’re not sure exactly what it is until you find it.

So, some of the best movies of all time come from very complex productions that, in industry terms, would be considered disastrous. Yet, maybe that chaos has allowed them to find unexpected beauty and weight.

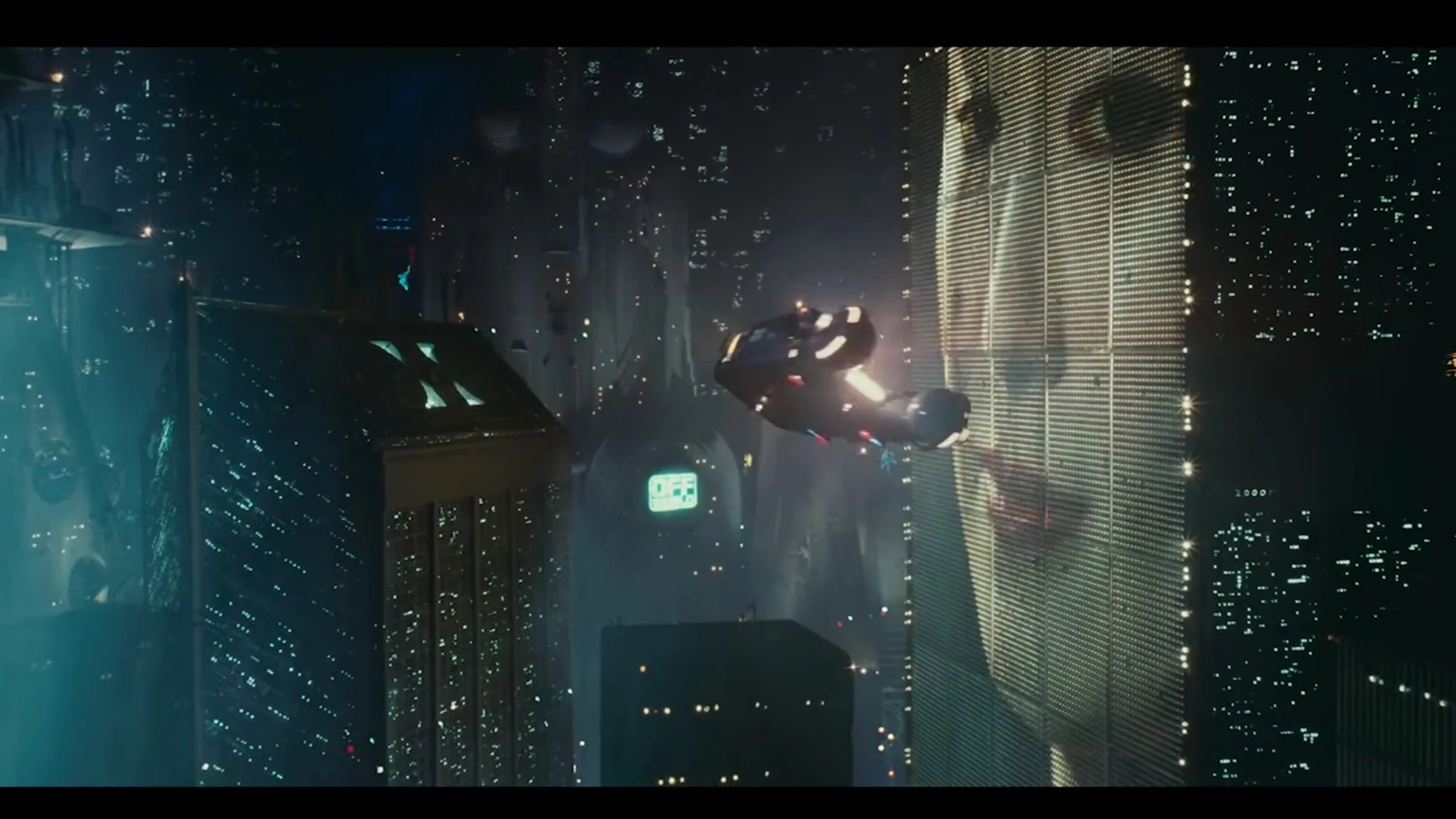

Blade Runner

Blade Runner is now considered a classic of science fiction movies, and it’s not easy to think of movies that have influenced design and art in stronger ways. But its production had been incredibly fraught. The script’s first version had been radically changed since neither director Ridley Scott nor Philip K. Dick, the author of the novel the film was based on, liked it. Multiple producers came together to put work on the movie, and many of them almost pulled out of financing it since work on it was slow and the director did not even go along with his crew. The thing with Blade Runner is that it’s not a very plot-driven movie at all: it’s more concerned with world-building, mood, and themes. In order to try and make it more streamlined, distributors forced a voice-over into the theatrical version, a choice that lead actor Harrison Ford hated so much that it’s easy to hear his lack of enthusiasm in the delivery. It took over a decade for Ridley Scott’s cut to come out: the director’s cut, and the Final Cut that came after that, embrace the ambiguity of the material, truly leaving plot behind to focus on mood, atmosphere and suspended themes and that is the version of the movie that is now accepted as a great film.

Annie Hall

Woody Allen had made a ton of comedies of extraordinary success, and in the mid-70s wanted to try different styles, and he was keen to put together something less outwardly funny, somehow closer to a drama. He and co-writer Marshall Brickman drafted a version of the movie that blended together a comedy, a mid-life crisis drama, and a murder mystery. Over time, the murder mystery element was completely dropped out, and principal photography started without a clear sense of the ending. It took a long time for the movie to find its shape, with a first cut lasting about two and a half hours, a shapeless film that left the creative team deeply dissatisfied, leading to two more weeks of reshoots. But it is very unlikely to figure this out watching the movie as it is right now, which feels pretty much perfect in its structure, yet also very light, and spontaneous, probably because, like life, some of its parts are assembled from sections that were not meant to fit together in the way that we see in the final movie, Annie Hall won an Academy Award for best movie, might be Woody Allen’s masterwork, and it feels like a perfectly cohesive piece of storytelling.

Mulholland Drive

Mulholland Drive was not even supposed to be a movie. David Lynch had been extremely successful for a while as a very respected “cult” director, but he only found legitimate mainstream success with Twin Peaks, one of the greatest TV shows of all time, and one of the unlikeliest hits in TV history, mixing together a pulpy crime mystery with an exploration of meaning in the quantum field. After the show ended, Lynch tried to go back to television with a couple of projects, but those were extremely niche affairs. Mulholland Drive at the very beginning was supposed to be a Twin Peaks spin-off, following Audrey Horne as she pursued her Hollywood dreams, but that did not work out. Still, the main idea morphed into a noir/thriller hybrid that Lynch developed for ABC. But the network did not like it, and they decided to pull the plug on the show. This, most of the time, just means that no one will ever see that pilot. But Lynch is not typical showrunner, and the French network Canal+ decided to finance a movie version of the pilot, buying the footage from ABC. Lynch shot additional material to turn the pilot into a feature film; one would think that it would be tricky to create something coherent and whole from this, but Lynch is the kind of artist that always adapts to the occasion, one that creates from a place of discovery, not from sticking to rigid plans. Indeed, Mulholland Drive is widely considered one of the greatest movies of all time, and one that feels extraordinarily coherent, complete, and whole.

Apocalypse Now

The making of Apocalypse Now is its own movie, so the disastrous production has a very well-known history. This is a case of a movie that finds its energy in the cracks of failure: by risking to create in a volatile, very fragile environment, Francis Ford Coppola managed to capture some of the most memorable and visceral images in cinema. Just like in the case of Blade Runner, the success of this lies in the choice of the filmmakers not to push the plot and narrative as much as diving into tone, world-building characters, and mood. In this way, the movie works as a wonderful tone piece, one that allows the viewer to explore their own feelings about war, leadership, imperialism, and heroism.

Star Wars and Jaws

The thing with massive successes is how easy it is to assume that they were always fated to be so. Star Wars is an excellent example of this, because up until its release, most of the people involved in its production, including writer/director George Lucas himself, assumed that the movie would be a massive failure. At a time when movie viewers seemed to gravitate around watching edgy, dark movies, it was hard to see how an earnest science fiction tale inspired by Flash Gordon and samurai movies could attract people. And Jaws was not in such a different place: the movie was a nightmare to shoot, because water is not easy to deal with, and the idea that a movie with very few stars, and a monster that barely featured in the first three quarters of the movie would be a success was not exactly an automatic thing. But the movies basically changed cinema, bringing back a desire for pure escapism that had always been a core feature of movie-going but had kind of disappeared for a while. The Blockbuster Podcast is a great way to dive into these stories (and the one behind Titanic, which could almost make it into this list).

It’s not exactly surprising that the above movies are all produced in Hollywood, where filmmakers are part of an industrial process. In other countries, where the film industry never quite managed to find as strict a structure, filmmakers had more chances to just embrace the chaos, like in these examples.

Breathless

The history of movies is in a lot of ways the history of the tools that have been used to make them. For a long time, to have a solid script and a very clear plan to make a movie was a very natural thing because to make most movies one had to build sets and take care of making them work so that location sound could work in them, and that massive lights could be installed to make sure that the slowish film stock available at the time could actually capture real life.

But then when lighter cameras, faster film and less cumbersome audio recording equipment became a reality, some filmmakers realise that it meant that they could change the way movies were shot completely. Jean Luc Godard spent his entire career trying to figure out how any new technology could aid to change the ways movies are made, and his first effort is still probably the best example of this. A spontaneous, raw story semi-improvised using handheld cameras and edited with constant use of jump-cuts, Breathless showed filmmakers that there was a new, very legitimate way to make movies, one that still inspired independent filmmakers to this day.

In The Mood For Love

Here, we go into another artist who crafts cinema on the go. Wong Kar-Wai has created beloved and memorable movies, and he almost never did this from a script. The director, together with his team of close collaborators led by legendary DOP Chris Doyle, shoots scenes for months, building stories and characters on the go. Actors need to be open to work this way, without a true sense of the future of the project they embarked on, a real showing of trust. In The Mood of Love is in many ways the apex of the filmmaker’s style and voice: a period piece that uses a pretty simple story as a pretext to dive into the space between people. It’s a movie where the space between the gaze of two lovers becomes a detailed landscape filled with tension; one gets the sense that in his openness to spontaneity, Kar-Wai has chosen some perfect moments that bring together the magic of the unexpected with a perfectly crafted cinematic symphony. It’s no wonder that this is a movie where even one of the outtakes has reached cult status.

Fitzcarraldo

This kind of list would not really work without Werner Herzog, one of the filmmakers that has embraced chaos more than any other in cinema. Fitzcarraldo is one of his best movies, and also one of the most controversial, as it really blurs the line between adventure and exploitation, while still remaining an indisputable masterpiece. Herzog shot a movie about a man in a quest to do something borderline impossible - dragging a steamship over a hill to reach a river that would lead to new riches - and decided to mirror that madness by actually dragging a steamship over that hill. The process, unsurprisingly, proved extremely difficult, and some of the local workers hired to work on the film got injured or even died during the production, during a time when on-set safety protocols were still very far ahead in the future. To make things just a tad more intense, the relationship between Herzog and lead actor Klaus Kinski was so confrontational that almost resulted in some of the locals planning a scheme to murder Kinski. The electricity of all this tension definitely hurt people, but thanks to Herzog's incredible ability to be present in his project, is still perfectly captured on film.

Now, for the exception that shames the rule:

Every Mission Impossible Movie since Ghost Nation

This is a bonus track in some ways. The Chris McQuarrie-led Mission: Impossible movies don’t have dramatic stories of plans going off the rails, even if Tom Cruise did get injured once while filming one of the many stunts in the movie, and COVID did delay work on Dead Reckoning Part 1 in a real way. Yet, I put these movies on the list because the way they are made is the ultimate example of how good it is to be nimble while making a movie, even a blockbuster.

I suggest listening to the Empire Spoiler Specials for each one of these movies because they are incredibly fascinating excursions into the process that led to these movies being made. Chris McQuarrie, the cast and every technician involved speaks of a very special mix of extreme precision and discipline in putting together each scene in the movie, while the stories are basically built on the fly. The movies have a general theme in mind, but there is no actual script as shooting goes: McQuarrie finds the movie as he’s making it together with his collaborators.

This is the method we have seen employed by some of the “auteurs” above, but it’s quite uncommon for blockbusters to be made with this method because the incredible budgets required to finish projects of this size make financiers very eager to get a sense that everything is under control at all time.

But control is a strange thing. It is not necessarily about having an entire plan in advance. Music is the best example of this: a great piece can come from months of writing a piece and then recording it. It can also come from great musicians very comfortable with improvising and connecting in a moment. There is no less control in the second case, but it might take a bit more courage to allow for that. What McQuarrie and Cruise have achieved is to create blockbusters in a very jazzy way: solving problems on the fly, almost embracing the idea of having problems without solutions to solve in order to create great moments of cinema. It’s not accidental that the latest movie in the franchise so far deals specifically with the tension between control and improvisation; technology and humanity, fear and courage.

Even if it’s hard to build a team capable of working in this way, these movies are proving influential. The John Wick series shares some elements of this philosophy, and hopefully many more will in the future.